PHILOSOPHY

LIVE MINDFULLY FOR THE HEALTH OF IT.

Wednesday, June 27, 2012

Self Concept

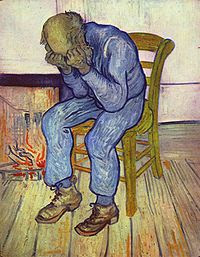

Vincent van Gogh: "I'd like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart"

How a genius feels: "I'm a nonentity, an eccentric, an unpleasant person"

March 30th is the birthday of Vincent van Gogh, born in Holland in 1853, a famous painter and also great letter-writer. His letters were lively, engaging, and passionate; they also frequently reflect his struggles with bipolar disorder.

He wrote: "What am I in the eyes of most people — a nonentity, an eccentric, or an unpleasant person — somebody who has no position in society and will never have; in short, the lowest of the low. All right, then — even if that were absolutely true, then I should one day like to show by my work what such an eccentric, such a nobody, has in his heart."

He wrote thousands of letters to his brother Theo over the course of his life. Theo's widow published the van Gogh's letters to her husband in 1913.

- Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle.

- Plato Greek author & philosopher in Athens (427 BC - 347 BC)

Image source: Vincent van Gogh's 1890 painting At Eternity's Gate. Wikipedia, public domain.

Monday, June 25, 2012

Robbie Burns: To A Mouse

- TO A MOUSE

- ON TURNING HER UP IN HER NEST WITH THE PLOUGH, NOVEMBER, 1785

I  EE, sleekit, cowrin, tim'rous beastie,

EE, sleekit, cowrin, tim'rous beastie, - Oh, what a panic's in thy breastie!

- Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

- Wi' bickering brattle!

- I was be laith to rin an' chase thee,

- Wi' murd'ring pattle!

II - I'm truly sorry man's dominion

- Has broken Nature's social union,

- An' justifies that ill opinion

- Which makes thee startle

- At me, thy poor, earth-born companion

- An' fellow-mortal!

III - I doubt na, whyles, but thou may thieve;

- What then? poor beastie, thou maun live!

- A daimen-icker in a thrave

- 'S a sma' request;

- I'll get a blessin wi' the lave,

- And never miss't!

IV - Thy wee-bit housie, too, in ruin!

- Its silly wa's the win's are strewin!

- An' naething, now, to big a new ane,

- O' foggage green!

- An' bleak December's winds ensuin,

- Baith snell an' keen!

V - Thou saw the fields laid bare an' waste,

- An' weary winter comin fast,

- An' cozie here, beneath the blast,

- Thou thought to dwell,

- Till crash! the cruel coulter past

- Out thro' thy cell.

VI - That wee bit heap o' leaves an stibble,

- Has cost thee mony a weary nibble!

- Now thou's turn'd out, for a' thy trouble,

- But house or hald,

- To thole the winter's sleety dribble,

- An' cranreuch cauld!

VII - But, Mousie, thou art no thy lane,

- In proving foresight may be vain:

- The best-laid schemes o' mice an' men

- Gang aft a-gley,

- An' lea'e us nought but grief an' pain,

- For promis'd joy!

VIII - Still thou art blest, compared wi' me!

- The present only toucheth thee:

- But och! I backward cast my e'e,

- On prospects drear!

- An' forward, tho' I cannot see,

- I guess an' fear!

Source:

http://www.poetry-archive.com/b/to_a_mouse.html

Robert Burns by Alexander Nasmyth

(By permission of the National Galleries of Scotland)

(By permission of the National Galleries of Scotland)

Monday, June 18, 2012

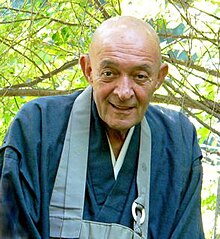

John Daido Loori - Zen Master

John Daido Loori

John Daido Loori, author, artist, Zen Master is the founder and abbot of Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York.

Under Daido Loori’s direction, Zen Mountain Monastery has grown to be one of the leading Zen monasteries in America, widely noted for its unique way of integrating art and Zen practice.

Daido Loori is also an award winning photographer and videographer, with dozens of exhibitions to his credit and a successful career in both commercial and art photography.

He has had 54 one-person shows, and his work has been exhibited in 118 group shows both in the United States and abroad.

His photographs have been published in leading photography magazines, including Aperture and Time Life Photography.

Sites:

http://www.johndaidoloori.org

http://www.mro.org/zmm/aboutus/abbot.php

| John Daido Loori | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | Zen Buddhism |

| School | Rinzai and Sōtō |

| Lineage | Mountains and Rivers Order (part of White Plum Asanga) |

| Other name(s) | Daido Loori |

| Dharma name(s) | Muge Daido |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | American |

| Born | June 14, 1931 Jersey City, NJ, United States |

| Died | October 9, 2009 (aged 78) Mount Tremper, NY, United States |

| Senior posting | |

| Title | Rōshi, abbot |

| Predecessor | Taizan Maezumi |

| Successor | Bonnie Myotai Treace, Geoffrey Shugen Arnold, Konrad Ryushin Marchaj |

| Religious career | |

| Website | www.mro.org/ johndaidoloori.org |

Part of a series on

Zen

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Daido_Loori

Sunday, June 17, 2012

Buddhists’ Delight

Renouncing the American way of life is not easy.

“I am still expecting something exciting,” Edmund Wilson

confided in his journal when he was in his mid-60s: “drinks, animated

conversation, gaiety: an uninhibited exchange of ideas.”

The balance and harmony that have formed the basis of the Buddhist tradition is attractive to many Americans who are converting to Buddhism

The fundamental insight of the Buddha (the Awakened One) is this: life consists of suffering, and suffering is caused by attachment to the self, which is in turn attached to the things of this world.

Only by liberating ourselves from the tyranny of perpetual wanting can we be truly free.

Buddhism is the fourth largest religion in the United States.

Dr. Paul D. Numrich, a professor of world religions and inter-religious relations, conjectured that there may be as many Buddhists as Muslims in the United States by now.

Professor Numrich’s claim is startling, but statistics (some, anyway) support it:

Many converts are what Thomas A. Tweed, in “The American Encounter With Buddhism,” refers to as “nightstand Buddhists” — mostly Catholics, Jews and refugees from other religions who keep a stack of Pema Chödrön books beside their beds.

Burned-out BlackBerry addicts attracted to its emphasis on quieting the “monkey mind”?

Casual acolytes rattled by the fiscal and identity crises of a nation that even Jeb Bush suggests is “in decline”?

Uncertain times make us susceptible to collective catastrophic thinking — the conditions in which religious movements flourish.

Or perhaps Buddhism speaks to our current mind-body obsession.

Dr. Andrew Weil, in his new book, “Spontaneous Happiness,” establishes a relationship between Buddhist practice and “the developing integrative model of mental health.”

This connection is well documented: at the Laboratory for Affective Neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin, researchers found that Buddhist meditation practice can change the structure of our brains — which, we now know from numerous clinical studies, can change our physiology.

The Mindful Awareness Research Center at U.C.L.A. is collecting data in the new field of “mindfulness-based cognitive therapy” that shows a positive correlation between the therapy and what a center co-director, Dr. Daniel Siegel, calls mindsight.

He writes of developing an ability to focus on our internal world that “we can use to re-sculpt our neural pathways, stimulating the growth of areas that are crucial to mental health.”

It was hard to concentrate at first, as anyone who has tried meditating knows: it requires toleration for the repetitive, inane — often boring — thoughts that float through the self-observing consciousness.

(Buddhists use the word “mindfulness” to describe this process; it sometimes felt more like mindlessness.)

But after a while, when the brass bowl was struck and we settled into silence, I found myself enveloped, if only for a few moments, in the calm emptiness of no-thought.

During the lectures, there was talk of “feelings,” “loving kindness” and “the inherent goodness of who we are” — tempered by good-natured skepticism.

(“Feel free to resume struggling with things,” a teacher concluded after a long “sitting.”)

But it wasn’t all about looking inward. There was also talk of issues I thought we had left behind.

“What’s affecting the world is the unhealthy state of mind — culture, environment and society,” a teacher reminded us: “violence, horror, bias, ecological catastrophe, the entire range of human pain.”

In Tibet, he noted, monasteries aren’t sealed off from the life around them but function as community centers.

The resistance to Chinese oppression has come largely from monks, who demonstrate and even immolate themselves in protest.

Engaged Buddhism — a concept new to me — has a tradition in the West.

Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, among its early American proponents, didn’t just cultivate their gardens.

Kerouac’s Buddha-worshiping “Dharma Bums” were precursors of the sexual revolution (their tantric “yabyum” rituals sound like fun); Ginsberg, a co-founder with Anne Waldman of the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, Colo., the first accredited Buddhist-inspired college in the United States, faced down the police at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago by using meditation as an instrument of passive resistance.

Reading “Buddhism in the Modern World,” a collection of essays edited by David L. McMahan, I was struck by the pragmatic tone of the contributors, their preoccupation with what Mr. McMahan identified as “globalization, gender issues, and the ways in which Buddhism has confronted modernity, science, popular culture and national politics.” Their goal is to make Buddhism active.

Perhaps it was simply the lesson of acceptance — and the possibility of modest self-transformation.

A teacher had said: “Don’t fix yourself up first, then go forth: the two are inseparable.”

To enact, or “transmit,” change in the world, we need to begin with ourselves and “learn how to have a skillful, successful, well-organized, productive life.”

Author:

James Atlas is the author of “My Life in the Middle Ages: A Survivor’s Tale.”

mentioned ...reading Sakyong Mipham’s “Turning the Mind Into an Ally”

Source:

Times Topic: Buddhism

Buddhists’ Delight

By JAMES ATLAS

Published: June 16, 2012

Saturday, June 16, 2012

“Realistic Action is Self-development”

Morita Therapy

“Realistic Action is Self-development”

Morita psychotherapy was developed by Japanese psychiatrist Shoma Morita in the early part of the twentieth century. He was chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Jikei University School of Medicine and was influenced by the psychological principles of Zen Buddhism.

His method was initially developed as a treatment for a type of anxiety neurosis called shinkeishitsu. In the latter part of this century the applications of Morita therapy have broadened, both in Japan and North America.

The Naturalness of Feelings (Arugamama)

If we find out that we have just won the lottery, we may be excited and happy. But if we find out about the death of a loved one, we may feel sadness and grief. Such feelings are natural responses to our life circumstances and we need not try to “fix” or “change” them.

Arugamama (acceptance of reality as it is) involves accepting our feelings and thoughts without trying to change them or “work through” them.

This means that if we feel depressed, we accept our feelings of depression. If we feel anxious, we accept our feelings of anxiety.

Rather than direct our attention and energy to our feeling state, we instead direct our efforts toward living our life well.

We set goals and take steps to accomplish what is important even as we co-exist with unpleasant feelings from time to time.

Feelings are Uncontrollable

There is an assumption behind many Western therapeutic methods that it is necessary to change or modify our feeling state before we can take action.

We assume that we must “overcome” fear to dive into a pool, or develop confidence so we can make a public presentation.

But in actuality, it is not necessary to change our feelings in order to take action. In fact, it is our efforts to change our feelings that often makes us feel even worse.

“Trying to control the emotional self willfully by manipulative attempts is like trying to choose a number on a thrown die or to push back the water of the Kamo River upstream. Certainly, they end up aggravating their agony and feeling unbearable pain because of their failure in manipulating the emotions.” -- Shoma Morita, M.D.

Once we learn to accept our feelings we find that we can take action without changing our feeling state. Often, the action-taking leads to a change in feelings. For example, it is common to develop confidence after one has repeatedly done something with some success.

Self-centeredness and Suffering

In Western psychotherapy there are a great many labels which purport to diagnose and describe a person’s psychological functioning - depressed, obsessive, compulsive, codependent.

Many of us begin to label ourselves this way, rather than investigate our own experience. If we observe our experience, we find that we have a flow of awareness which changes from moment to moment. When we become overly preoccupied with ourselves, our attention no longer flows freely, but becomes trapped by an unhealthy self-focus. The more we pay attention to our symptoms (our anxiety, for example) the more we fall into this trap.

When we are absorbed by what we are doing, we are not anxious because our attention is engaged by activity. But when we try to “understand” or “fix” or “work through” feelings and issues, our self-focus is heightened and exercised. This often leads to more suffering rather than relief. How can we be released from such self-focused attention?

“The answer lies in practicing and mastering an attitude of being in touch with the outside world. This is called a reality-oriented attitude, which means, in short, liberation from self-centeredness.” -- Takahisa Kora, M.D.

“The answer lies in practicing and mastering an attitude of being in touch with the outside world. This is called a reality-oriented attitude, which means, in short, liberation from self-centeredness.” -- Takahisa Kora, M.D.

Ultimately, the successful student of Morita therapy learns to accept the internal fluctuations of thoughts and feelings and ground his behavior in reality and the purpose of the moment.

Cure is not defined by the alleviation of discomfort or the attainment of some ideal feeling state (which is impossible) but by taking constructive action in one’s life which helps one to live a full and meaningful existence and not be ruled by one’s emotional state.

The methods used by Morita therapists vary. In Japan, there is often a period of isolated bedrest before the patient is exposed to counseling, instruction and work therapy.

In the U.S., inpatient Morita therapy is generally unavailable, and most practitioners favor a counseling or educational approach, the emphasis of which is on developing healthy living skills, learning to work with our attention, and taking steps to accomplish tasks and goals.

For this reason, Morita therapy is sometimes referred to as the psychology of action.

“In general, the stronger we desire something, the more we want to succeed, and the greater our anxiety about failure.

Our worries and fears are reminders of the strength of our positive desires....

Our anxieties are indispensable in spite of the discomfort that accompanies them.

To try to do away with them would be foolish.

Morita therapy is not really a psychotherapeutic method for getting rid of “symptoms”.

It is more an educational method for outgrowing our self-imposed limitations.

Through Morita methods we learn to accept the naturalness of ourselves.”

-- David Reynolds, Ph.D.

Source:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)